Harrowing and unflinching yet inspiring, the Royal Academy of Arts first major retrospective of Anselm Kiefer’s work is no walk in the park.

Born in Germany in 1945, Anselm’s generation had the gruelling task of recovering from the war and facing up to the horrors of Nazi rule. Yet as the country wished to forget its horrific past, Kiefer’s art refused to follow this example and chose instead to confront it face on, highlighting it as an ugly chapter in the nation’s history.

Dark reflection

A chronological reflection on his work, the exhibition is an extensive and broad contemplation of his art that spans over forty years. As shocking as it was then, Kiefer’s fascination with Germany’s Nazi past is showcased the moment you arrive, demonstrated with his 1971 painting Ice and Blood. An eerie watercolour with a figure at the centre giving a Nazi salute in the middle of barren and snowy field, which leaves you in a queasy state of mesmerisation.

This confrontation intensifies as you slowly make your way through each room, notably increasing as he touches upon the subject of the Holocaust. It is very clear in the grand painting ‘Sulamith’ (1983), which was inspired by a Paul Celan poem ‘Death Fugue’, written in a concentration camp. The poem is adjacent to the piece, adding to the already gloomy and unsettling scene and is centred on Sulamith, a Jewish girl killed in a death camp because of her dark ‘ashen hair’. Kiefer’s portrayed crypt composed of oil, emulsion, woodcut, shellac, acrylic and straw is inscribed with the name ‘Sulamith’ at the top left corner and resembles the chamber where she would have been killed. The architecture that is intended to honour Nazi heroes has been transformed into a memorial for their victims.

Material context

Grand in stature, his work encompasses a whole breadth of material from lead, gold leaf, sand and copper wire to straw, wood and diamonds. However, these materials are often not used for their aesthetic qualities but for their inherent meaning to his work. The RA describes lead for instance, as being of ‘fundamental importance to his work: he believes that it is the only material heavy enough to carry the weight of human history’.

His subjects include everything from the Holocaust, the works of Paul Celan, the architecture of Albert Speer and even Mythology. He makes bold statements on a number of issues in incredibly original ways, yet contextualising is always necessary in order to fully appreciate his aims.

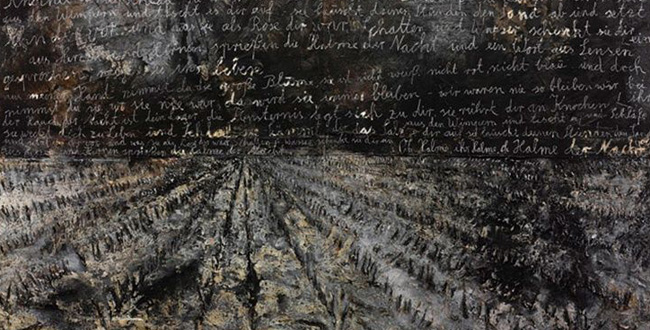

The Morgenthau paintings (2013) are a reference to US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., who devised the plan to transform Germany into a pre-industrial state in order to limit any future dangers. The paintings are of bleak wheat fields, representing a reality that could have been if the plan had come to fruition.

Kiefer is not an easy artist to appreciate. Not in the sense of whether his art has any merit, but more with the fact that his subject-matter and technique are uncomfortable and always flirt with the macabre. Nothing, it seems, is done purely for aesthetic purpose, with each piece being a statement in one way or another. Even describing his work as declamatory feels like an understatement, as these raw unadulterated projects come out at you from the walls, becoming a total attack on sensorial awareness.

Immersion

The RA’s organisation of this exhibition is careful and deliberate, because as you move through each room, you become totally immersed in Kiefer’s work. While it begins with his paintings, it gradually moves into three-dimensional pieces becoming more and more alive. This breaks the original dichotomy between the audience and the art, where you are forced to renegotiate your relationship with the displays.

This transition is brought out in Room Six, which features his Untitled (2006-08) piece, consisting of brambles, dead leaves and ash set against a forest backdrop all contained within a vitrine. This is taken one step further in the octagonal gallery with his latest piece (made explicitly for this exhibition) Ages of the World (2014). Essentially, it’s a heap of abandoned canvases stacked on top of each other, littered with rubble and other paraphernalia, but it’s simply spectacular, possessing an otherworldly quality to it that touches on the sublime.

The gradual transformation becomes absolute by the final room, which is composed of literal walls of his work, fully enclosing you in the art. It’s an outstanding journey, as your interactions with the pieces constantly shift, eventually becoming part of the work itself.

Bold and ambitious, each room presents something fresh and thoroughly surprising. Diversity, for lack of a better word, sums up a large part of Anselm Kiefer’s work. There is a certain deathly vitality to his work; a sense that it’s brimming with life whilst dying at the same time. The exhibition really leaves a mark on you, even once you’ve left the RA. His work is admirable in its unwavering and provocative nature, and shows how art can be the source of any important societal discussion.

Intense and powerful, this exhibition is a reminder of why Anselm Kiefer is one of the most important living artists today.

![[Image - RAA]](https://www.fqmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/08f61c52357dcc6d2503bfea790efe4d.jpg)