A contemplation on one of the most socially, culturally and politically turbulent eras in modern history, Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album is a frank but insightful exploration of American life in the 1960’s.

His photographic work has been described as ‘small movies, still photographs made on the sets and locations of imagined films in progress’, and present a candid perspective of America between 1961 and 1967. Hosted at the Royal Academy of Arts, this is a fantastic glimpse into one of the most significant decades in the 20th century.

The RA boasts over 400 original photographs taken by Hopper, which were personally selected by him for his 1970 exhibition at the Fort Worth Art Center in Texas. It wasn’t until his death in 2010 that these original prints were rediscovered and it’s the first time that this body of work has been seen in the UK.

The exhibition is split into numerous rooms, each with its own thematic focus that ranges from celebrities, contemporary artists, the civil rights movement and the rising hippy movement. The photographs serve both as a personal perspective and as a documented reflection of the times, jumping from portraits of friends to much larger social issues. The photos however, are not solely set in America, with areas such as London and Peru used as locations, whilst there is also a fairly large selection set in Mexico.

An artist’s passion

Hopper was not a trained photographer, but instead had a deep passion for the art; bringing his camera everywhere he went which revealed a more curious and sensitive side to his persona. This isn’t the manic Hopper people have come to know from his films, but a more pensive and thoughtful character.

Hopper was not a trained photographer, but instead had a deep passion for the art; bringing his camera everywhere he went which revealed a more curious and sensitive side to his persona. This isn’t the manic Hopper people have come to know from his films, but a more pensive and thoughtful character.

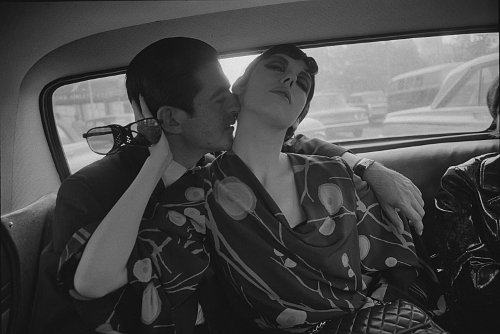

This is evident in the photos he took, which boast a great level of realism in them, with everything from stark, to funny or tragic. Having taken over 18,000 photos in this period, his subject matter ranges from the despondent to the rich and glamorous, revealing an inherent intrigue for all walks of life.

There are of intimate portraits of some of the famous names at the time, from Paul Newman, to Jane Fonda, and Bill Cosby that favour naturalism over glamour. Having been in extensive artistic circles, visitors can catch glimpses of figures such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein and more. There is also an extensive exploration of the important musicians of the time including Ike and Tina Turner, Jefferson Airplane, The Byrds and others.

The great thing about these photos is that they take away that imaginary line between celebrity and human. Instead of celebrating them for whatever they are famous for, they are simply snapshots of real people at their most vulnerable. The most striking in this category is definitely of Ike and Tina Turner, which is a warm and joyous photo of the couple, which juxtaposes with the darker and abusive reality of their relationship.

Capturing turbulent times

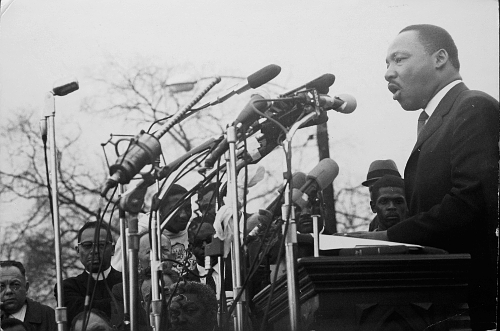

There are also poignant looks at the important social changes the sixties went through, from the civil rights movement to the hippy and beatnik movements.

The exhibition covers much of the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery during the African American Civil Rights Movement, having accompanied Martin Luther King throughout the process. These photographs reveal a more divided and turbulent time in America, where racial tensions were high and the fight for equality was often a costly one.

Hopper doesn’t really make a statement on the issue, instead presenting it in its stark nature for audiences to make their own judgments. Some of them even mirror the Vietnam conflict of the time, possessing a sort of apocalyptic quality to them, where whilst America was fighting its wars abroad, it was also ruptured by a number of internal conflicts.

On the other end of the spectrum, it equally explores the burgeoning countercultural movements, with everything from demonstrations, rallies, ‘love-in’s’ and more. There is also considerable work focused on the Hell’s Angels, who were closely associated with many of the countercultural groups of the time and had even been hired as security for festivals.

On the other end of the spectrum, it equally explores the burgeoning countercultural movements, with everything from demonstrations, rallies, ‘love-in’s’ and more. There is also considerable work focused on the Hell’s Angels, who were closely associated with many of the countercultural groups of the time and had even been hired as security for festivals.

Hopper’s fascination with motorcycles would see more prominence in later years, especially with the making of the classic road film Easy Rider. A clip of the latter is also on circulation at the end of the exhibition, serving as a poignant conclusion as the film represents in many ways, the end of this era.

One room however, that was slightly disappointing was the final room which featured a number of Hopper’s more experimental work, which jarred in relation to the rest of the exhibit. While the previous works were deeply realistic and served as a great document to the times, this last part felt out of place as despite still being interesting, lessened the impact of the previous sections.

In the modern age, people see the sixties as a mythical era, one that seems eons away but is in fact not too long ago. In lieu of iconic events such as Woodstock or the Moon landing, we paint the decade with a brush of idealism. However, whilst some of this is true, Dennis Hopper manages to shed a different light on this period with his sincere and honest photography. It’s a fantastic reflection on this era and the RA have been incredibly fortunate to be able bring this to the UK. One of the most powerful and striking collections, as Hopper said of his work: ‘I wanted to document something, I wanted to leave something that I thought would be a record of it, whether it was Martin Luther King, the hippies, or whether it was the artist.’

All images are credit – The Hopper Art Trust © Dennis Hopper, courtesy The Hopper Art Trust. www.dennishopper.com, including Double Standard, Dennis Hopper 1961, Irving Blum and Peggy Moffitt, Dennis Hopper, 1964 and Martin Luther King, Jr, Dennis Hopper, 1965.

![[Image - Dennis Hopper, Double Standard, 1961]](https://www.fqmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/f50c152c7848dac24210d3ad3ad22154.jpg)