Anorexia makes up 10 per cent of UK eating disorders. Here’s one dad’s story of handling his daughter’s battle with it.

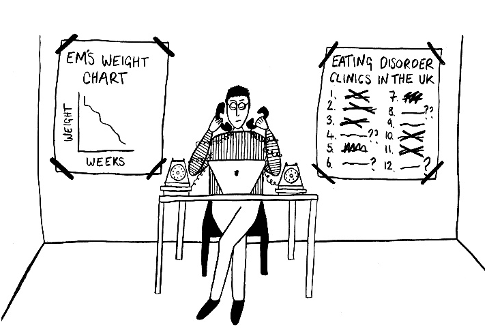

My daughter, Emily, developed anorexia nervosa in 2012, when she was sixteen years old. The illness lasted six full-blown years and during that period, she was unable to take her A-levels, spent a year in three eating disorder clinics, self-harmed, threatened suicide and suffered from severe depression and anxiety.

Her weight dropped to 70 pounds and at her lowest point she had a tube inserted into her nose to give her the nutrition she needed to stay alive.

It was a challenging time to be a dad, to say the very least. But this is what it taught me.

Learn to speak Irrational

Anorexia is a mental illness. Like all sicknesses of the mind, the brain stops functioning properly. It would tell Emily she was fat, every hour of every day. Emily believed it.

When you are communicating with somebody who has a mental illness, they do not always respond well to logical arguments. “Emily, if you stop eating, your bones will become weaker and weaker,” seems like a very sensible thing to say, but you might as well be speaking a foreign language.

Listening, empathising, encouraging, hugging and holding hands are often more effective tactics. An emotional, irrational approach often trumps a rational one.

Just do it!

In one respect, anorexia should be treated just like any other serious illness. If you develop cancer, there is a well-established procedure for trying to counter the illness.

However, trying to conquer an eating disorder is much more a case of trial and error. Finding the right path to recovery is tricky, and so it’s often up to the parents to pick up the phone, do their homework, be pro-active and try and find the route that will give your child the best chance of success. Act rather than sit back and hope!

Look at yourself

This is not a selfish thing. This is a must. Anorexia proved to be a brutal, unforgiving and relentless enemy. Cunning, devious, manipulative. My wife, Mel, and I could not take our eye off the ball for a minute.

So we had to divide and conquer, play to one another’s strengths, taking it in turn to relax and recuperate. For me, that meant taking our black Labrador for a walk or having a couple of pints down the pub. For Mel, it was a night out with her girlfriends or an afternoon shopping.

Mark Simmonds talks candidly about his own experiences with mental ill health both as a sufferer and as a carer in his first book Breakdown and Repair. Follow him @mentalhealthmark.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.